Positive school leadership that supports teacher wellbeing

Rachel Cann, University of Auckland

“Teachers are the most precious resource that we have in our education system, but too often we fail to treat them as ‘taonga’ [treasures] but as a means to an end.” (Cameron et al., 2007)

Concerns about poor teacher wellbeing, and the resulting consequences for education systems in terms of low-quality teaching and teachers leaving the profession, are global issues. In New Zealand, teachers’ concerns about their working conditions and wellbeing were evident in the ‘megastrike’ of mid-2019. There is a plethora of research investigating negative states of teacher wellbeing (for example, teacher burnout), yet in comparison little research investigates how to increase teacher wellbeing.

My research

For my masters’ thesis, I focused on the ways in which teacher wellbeing could be enhanced. I used the lens of positive psychology, which seeks to “understand and build the factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to flourish.” The research to date on enhancing teacher wellbeing generally focuses on changing individual teachers’ habits or actions through interventions such as learning mindfulness, or stress management skills. However, there is little research on how the school environment could be optimised to enhance teacher wellbeing. Therefore, I decided to focus on the role that schools can play in enhancing teacher wellbeing through answering the research question: How do educational leadership practices influence teacher wellbeing?

Data collection

The research was conducted at one secondary school in an urban area of New Zealand. Two phases of data collection were employed – a survey that measured teacher wellbeing, followed by interviews with six teachers. The survey used a scale based on positive psychology theory (the PERMA-profiler) that generated a teacher wellbeing score between 1 and 10. The scores were used to select three ‘high wellbeing’ and three ‘low wellbeing’ teachers, in order conduct a comparative case study, as understanding the extremes of teachers experiences of wellbeing allowed for a greater understanding of the phenomenon.

The six case study teachers participated in interviews, where I explored teachers’ own definitions of wellbeing, the actions they took to enhance their wellbeing, and their perceptions about school influences on their wellbeing. The following sections summarise the key findings.

Teachers’ definitions of wellbeing and wellbeing habits

Most teachers defined wellbeing as broad and multidimensional, encompassing mental, emotional and physical aspects. The main difference between the high wellbeing and low wellbeing teachers was the way in which high wellbeing teachers were able to talk enthusiastically about examples that illustrated their high wellbeing, such as self-care habits and healthy coping strategies to manage stress. For example, one high wellbeing teacher noted:

“Keeping up my fitness really helps with those endorphins, and you know, I just feel better after my run and keeping fit, it kind of de-stresses me at the end of the day” (Teacher F).

In contrast, low wellbeing teachers tended to comment on having decreased their time spent on hobbies or exercise, and were more prone to ruminating about stressful events.

Circumstances that impacted wellbeing

Teachers’ individual circumstances varied, and impacted wellbeing in different ways – for example, family could be a source of stress or a source of support. Teachers also commented on how school-based factors such as supportive colleagues and good relationships with students had positive impacts on their wellbeing. A good work-life balance was mentioned as important for wellbeing, but the degree to which teachers felt a sense of agency around this varied. Some teachers felt able to put boundaries around work, but others felt school work encroached too much on their home life.

School leaders’ actions that enhance teacher wellbeing

Whilst there are not distinct boundaries between the actions that teachers can take to enhance their own wellbeing and the actions that are the responsibility of schools, there were three clear themes that emerged about how school leaders’ actions impact teacher wellbeing.

1. The importance of teachers feeling that they are valued

Teachers all talked about the importance of appreciation, recognition, and feeling valued in contributing to their wellbeing. High wellbeing teachers were more likely to comment positively about this, for example leaders’ listening to their views:

“I think they listen to teacher voice, and I think they do value it” (Teacher D).

The same teacher commented on the effects of a lack of recognition in a previous school:

“I kind of really worked hard to make it a wonderful department, we got brilliant results for our students, but still I didn’t get any promotion within that school, and that was a little bit disheartening” (Teacher D).

2. The impact of meaningful professional development

All teachers referred to the potential for professional development to positively impact their wellbeing, with many discussing the sense of achievement they experienced through their own personal and professional growth.

“[The leaders are] really challenging us with that reflective… being reflective on our own practice, you know, that’s stuff’s good” (Teacher C).

However, low wellbeing teachers more frequently expressed a lack of understanding of the content of professional development, or the rationale behind it:

“We are encouraged to just kind of take it step by step, but I don’t know if I fully understand the concepts?” (Teacher B).

3. Enabling teacher agency in decision making and changes

There were clear differences between the low wellbeing and high wellbeing teachers in terms of the degree of agency that they felt in decision making and changes occurring in the school. High wellbeing teachers were confident to approach leaders to ask questions and felt they were listened to:

“We feel part of the solution rather than just being, you know, symbols of the problem.” (Teacher C)

However, low wellbeing teachers more commonly expressed that their views were not taken into account, and they disagreed with the changes occurring in the school:

“Too much change and not seeing the reasons for change. Or it could be someone’s reason for change, but the evidence doesn’t back that up” (Teacher E).

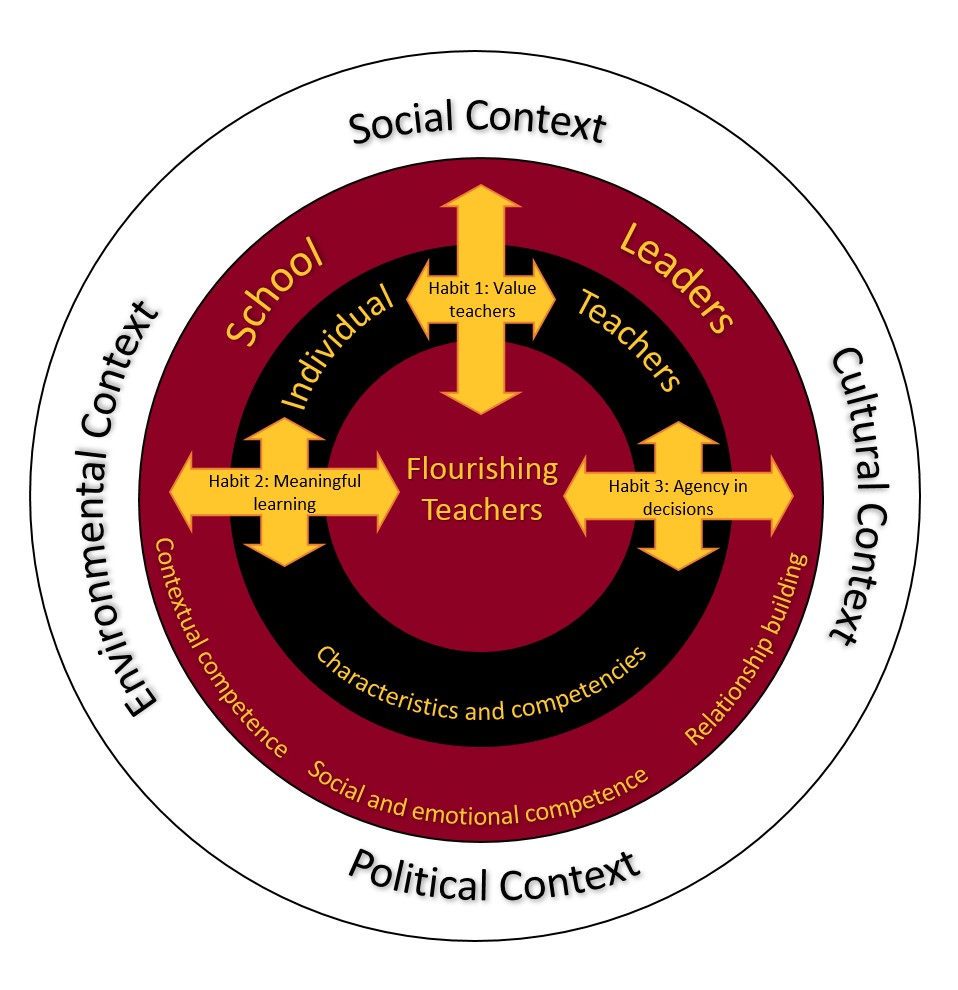

Positive school leadership model

The three themes above were used to construct a new model of positive school leadership that represents the actions that school leaders can take (and develop into habits) that enhance teacher wellbeing.

Flourishing teachers are placed at the centre of the model, with the surrounding circles and arrows indicating the factors that enable teacher to flourish.

The next level is the individual teachers, and their characteristics and competencies – for example, a teacher’s level of optimism, or coping skills can influence their wellbeing.

The next level are school leaders, and three areas that influence their interactions with teachers: contextual competence (a leader’s ability to understand and respond to context), social and emotional competence, and relationship building.

The outer circle represents contexts that are often outside of teachers or leader’s direct control, for example political context can refer to educational policy.

The three arrows in the model represent leadership habits (actions repeated regularly over time) that can positively influence teachers’ wellbeing:

- ensuring teachers feel that they are valued,

- providing meaningful professional development, and

- enabling teacher agency in decision making and changes.

The three habits are shown interacting with both leaders and teacher’s characteristics and competencies – for example school leaders’ skills in areas such as relationship building, affect the degree to which they are able to successfully enact the habits that can improve teacher wellbeing, and what makes professional development meaningful to a teacher will depend on their existing skills and their own needs. (More information on the model can be found in my thesis here and a journal article here).

Why these findings are important

Teacher wellbeing is not only important to the teachers themselves, but also to the profession as a whole, and ultimately for the students in our education system. Improving teacher wellbeing has the potential to help reduce attrition and ensure quality teaching. A focus on teacher wellbeing has also been identified as a first step in whole-school approaches to improving the wellbeing of students. Whilst some research has explored interventions aimed at improving teacher wellbeing, they are predominantly focused on changing individual teachers’ skills, habits and routines, through practices such as mindfulness, building resilience and managing stress. More research is needed on how school cultures and educator interactions influence wellbeing. This research reinforces the importance of positive relationships for wellbeing, and demonstrates that the quality of leader-teacher interactions has a considerable influence on teacher wellbeing.

Rachel Cann is a PhD student at the University of Auckland. She completed her Master’s thesis on the actions that educational leaders can take to help enhance teacher wellbeing. She continues to explore teacher wellbeing for her doctoral studies, in particular using the perspectives of positive psychology and social network theory. Previously, Rachel was a head of science in an Auckland secondary school, and has also led cross-curricular teams of teachers for project-based learning, pastoral care, and teaching as inquiry.