Power of a school

Code switching family vs school loyalty.

School systems treat all the same

Changes for us doubles and halves

housing built for families of 4

Aka Matatupu Teach First

Maia

Power of a school

Code switching family vs school loyalty.

School systems treat all the same

Changes for us doubles and halves

housing built for families of 4

Aka Matatupu Teach First

Maia

Inclusive Leadership (Diversity works) In the constant search for inclusiveness, leaders are required to learn how to benefit from motivated followers who feel safe to bring their whole selves to the workplace. Inclusive leadership helps current and future leaders to manage different viewpoints and transform dissent and disagreement into value for organisational growth. In this three-hour workshop, we cover:

The role of leaders in diversity and inclusion

The psychological foundations of inclusive leadership

Differences between inclusive leadership and other leadership styles

Inclusive leadership skills and traits

.

.

Last time I wrote about how we often over think our roles and that this in turn creates problems that aren’t even there. It was part of a piece about slowing things down, especially at this time of term.

Recently I was part of a discussion regarding the dilemma that we all face – when do we find time to show leadership when we seem to be in constant management mode.

As principals, we are expected to be leaders yet we tend to spend our lives in the day to day grind and minutiae of school existence rather than floating above it, being ultra visionary and seeing the “big picture”.

Perhaps it’s time to get off this hamster wheel of doubt created by over thinking the management vs leadership debate.

Surely they co-exist, not only side by side, but together like osmosis, flowing into one another; at times morphing into pure management while at other times being pure leadership, but more often than not just a colourful mixture of both.

Apparently it was Theodore Roosevelt who said, “people don’t care what you know until they know that you care”. This to me, is one of the real touchstones of what being a principal is all about.

Effectively this means that the people that you get paid to lead, or manage, don’t care about either of these terms. They just care that you care.

When you do enough in your school to show that you care consistently to a diverse group of humans, then that is both great leadership and great management.

There are times when you need to manage. This might feel like you’re knee deep in the veritable crappolla generated by others. But the fact that you’re there, and you’re showing you’ve got something more than a heartbeat, is in itself great leadership.

Equally there are times when you lead. And this might feel like you are able to fly above the same crapolla generated by others. But the fact that you can see what is going on with eyes like a falcon is also in itself great management.

So don’t over complicate it, and definitely don’t worry about it, you’ll be where you need to be, when you need to be, and that is good enough.

Steve

Rachel Cann, University of Auckland

“Teachers are the most precious resource that we have in our education system, but too often we fail to treat them as ‘taonga’ [treasures] but as a means to an end.” (Cameron et al., 2007)

Concerns about poor teacher wellbeing, and the resulting consequences for education systems in terms of low-quality teaching and teachers leaving the profession, are global issues. In New Zealand, teachers’ concerns about their working conditions and wellbeing were evident in the ‘megastrike’ of mid-2019. There is a plethora of research investigating negative states of teacher wellbeing (for example, teacher burnout), yet in comparison little research investigates how to increase teacher wellbeing.

For my masters’ thesis, I focused on the ways in which teacher wellbeing could be enhanced. I used the lens of positive psychology, which seeks to “understand and build the factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to flourish.” The research to date on enhancing teacher wellbeing generally focuses on changing individual teachers’ habits or actions through interventions such as learning mindfulness, or stress management skills. However, there is little research on how the school environment could be optimised to enhance teacher wellbeing. Therefore, I decided to focus on the role that schools can play in enhancing teacher wellbeing through answering the research question: How do educational leadership practices influence teacher wellbeing?

The research was conducted at one secondary school in an urban area of New Zealand. Two phases of data collection were employed – a survey that measured teacher wellbeing, followed by interviews with six teachers. The survey used a scale based on positive psychology theory (the PERMA-profiler) that generated a teacher wellbeing score between 1 and 10. The scores were used to select three ‘high wellbeing’ and three ‘low wellbeing’ teachers, in order conduct a comparative case study, as understanding the extremes of teachers experiences of wellbeing allowed for a greater understanding of the phenomenon.

The six case study teachers participated in interviews, where I explored teachers’ own definitions of wellbeing, the actions they took to enhance their wellbeing, and their perceptions about school influences on their wellbeing. The following sections summarise the key findings.

Most teachers defined wellbeing as broad and multidimensional, encompassing mental, emotional and physical aspects. The main difference between the high wellbeing and low wellbeing teachers was the way in which high wellbeing teachers were able to talk enthusiastically about examples that illustrated their high wellbeing, such as self-care habits and healthy coping strategies to manage stress. For example, one high wellbeing teacher noted:

“Keeping up my fitness really helps with those endorphins, and you know, I just feel better after my run and keeping fit, it kind of de-stresses me at the end of the day” (Teacher F).

In contrast, low wellbeing teachers tended to comment on having decreased their time spent on hobbies or exercise, and were more prone to ruminating about stressful events.

Teachers’ individual circumstances varied, and impacted wellbeing in different ways – for example, family could be a source of stress or a source of support. Teachers also commented on how school-based factors such as supportive colleagues and good relationships with students had positive impacts on their wellbeing. A good work-life balance was mentioned as important for wellbeing, but the degree to which teachers felt a sense of agency around this varied. Some teachers felt able to put boundaries around work, but others felt school work encroached too much on their home life.

Whilst there are not distinct boundaries between the actions that teachers can take to enhance their own wellbeing and the actions that are the responsibility of schools, there were three clear themes that emerged about how school leaders’ actions impact teacher wellbeing.

1. The importance of teachers feeling that they are valued

Teachers all talked about the importance of appreciation, recognition, and feeling valued in contributing to their wellbeing. High wellbeing teachers were more likely to comment positively about this, for example leaders’ listening to their views:

“I think they listen to teacher voice, and I think they do value it” (Teacher D).

The same teacher commented on the effects of a lack of recognition in a previous school:

“I kind of really worked hard to make it a wonderful department, we got brilliant results for our students, but still I didn’t get any promotion within that school, and that was a little bit disheartening” (Teacher D).

2. The impact of meaningful professional development

All teachers referred to the potential for professional development to positively impact their wellbeing, with many discussing the sense of achievement they experienced through their own personal and professional growth.

“[The leaders are] really challenging us with that reflective… being reflective on our own practice, you know, that’s stuff’s good” (Teacher C).

However, low wellbeing teachers more frequently expressed a lack of understanding of the content of professional development, or the rationale behind it:

“We are encouraged to just kind of take it step by step, but I don’t know if I fully understand the concepts?” (Teacher B).

3. Enabling teacher agency in decision making and changes

There were clear differences between the low wellbeing and high wellbeing teachers in terms of the degree of agency that they felt in decision making and changes occurring in the school. High wellbeing teachers were confident to approach leaders to ask questions and felt they were listened to:

“We feel part of the solution rather than just being, you know, symbols of the problem.” (Teacher C)

However, low wellbeing teachers more commonly expressed that their views were not taken into account, and they disagreed with the changes occurring in the school:

“Too much change and not seeing the reasons for change. Or it could be someone’s reason for change, but the evidence doesn’t back that up” (Teacher E).

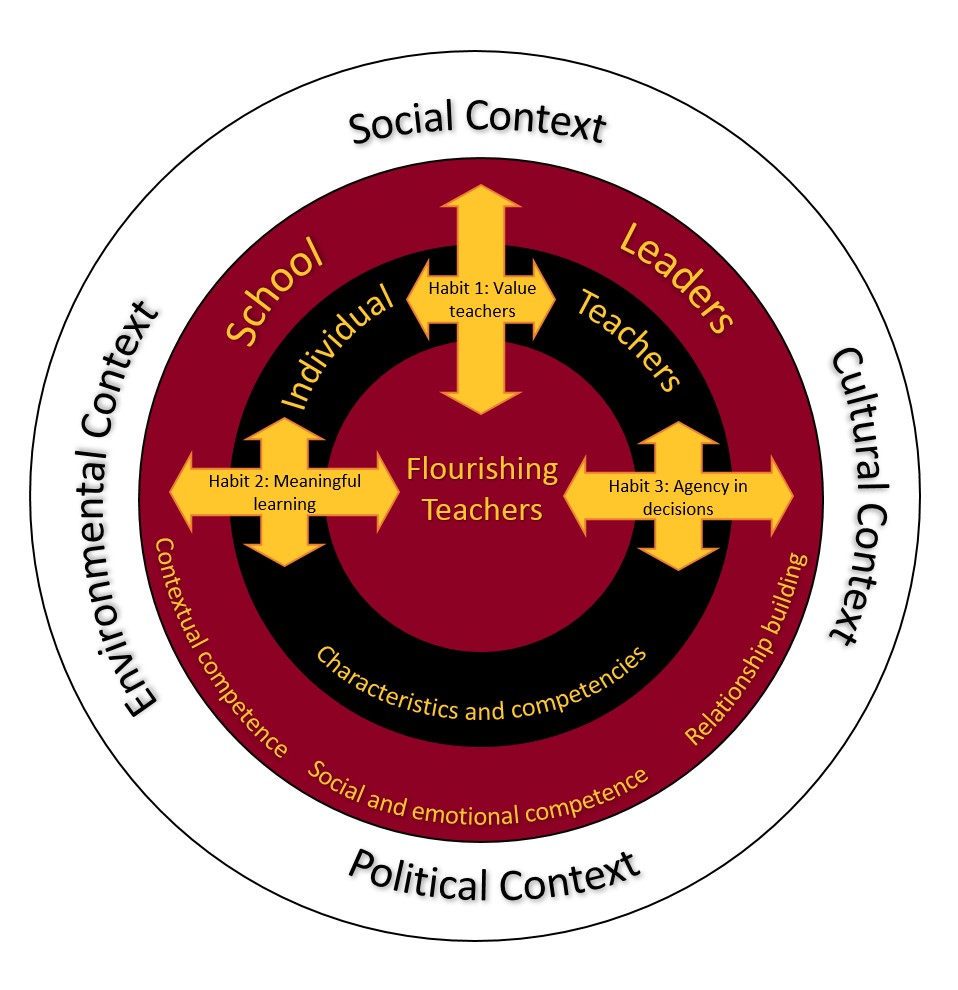

The three themes above were used to construct a new model of positive school leadership that represents the actions that school leaders can take (and develop into habits) that enhance teacher wellbeing.

Flourishing teachers are placed at the centre of the model, with the surrounding circles and arrows indicating the factors that enable teacher to flourish.

The next level is the individual teachers, and their characteristics and competencies – for example, a teacher’s level of optimism, or coping skills can influence their wellbeing.

The next level are school leaders, and three areas that influence their interactions with teachers: contextual competence (a leader’s ability to understand and respond to context), social and emotional competence, and relationship building.

The outer circle represents contexts that are often outside of teachers or leader’s direct control, for example political context can refer to educational policy.

The three arrows in the model represent leadership habits (actions repeated regularly over time) that can positively influence teachers’ wellbeing:

The three habits are shown interacting with both leaders and teacher’s characteristics and competencies – for example school leaders’ skills in areas such as relationship building, affect the degree to which they are able to successfully enact the habits that can improve teacher wellbeing, and what makes professional development meaningful to a teacher will depend on their existing skills and their own needs. (More information on the model can be found in my thesis here and a journal article here).

Teacher wellbeing is not only important to the teachers themselves, but also to the profession as a whole, and ultimately for the students in our education system. Improving teacher wellbeing has the potential to help reduce attrition and ensure quality teaching. A focus on teacher wellbeing has also been identified as a first step in whole-school approaches to improving the wellbeing of students. Whilst some research has explored interventions aimed at improving teacher wellbeing, they are predominantly focused on changing individual teachers’ skills, habits and routines, through practices such as mindfulness, building resilience and managing stress. More research is needed on how school cultures and educator interactions influence wellbeing. This research reinforces the importance of positive relationships for wellbeing, and demonstrates that the quality of leader-teacher interactions has a considerable influence on teacher wellbeing.

Rachel Cann is a PhD student at the University of Auckland. She completed her Master’s thesis on the actions that educational leaders can take to help enhance teacher wellbeing. She continues to explore teacher wellbeing for her doctoral studies, in particular using the perspectives of positive psychology and social network theory. Previously, Rachel was a head of science in an Auckland secondary school, and has also led cross-curricular teams of teachers for project-based learning, pastoral care, and teaching as inquiry.

ISSUE 39, 13 NOVEMBER 2020

Kia ora e te whānau

This week I had the privilege of attending the Te Akatea Māori Principals’ Conference in Auckland.

Dr Papaarangi Reid’s wero to the conference was a powerful challenge for principals, ‘We need pākehā to develop a critical consciousness of racism and disadvantage’, she said.

As a pākehā principal myself, seeing past my own ‘whiteness’ is a challenge. Pākehā hold an experience and knowledge of the world that is informed by their status as the majority and colonising culture and its associated privilege.

As a benefactor of this privilege it is hard to see past its affordances.

There is little cultural dissonance for Pākehā daily life in Aotearoa. Pākehā live in a society that is affirming of their culture. From birth, Pākehā are conditioned by an ideology that reinforces western and Eurocentric norms. These norms are found in the interactions of daily life, in our schools and what they teach, in textbooks, politics, movies, advertising, holiday celebrations, words and phrases.

Pākehā do not see themselves in racial terms because they are the majority.

This is where Dr Reid’s wero becomes significant. If we are to grow schools and educators to be genuine Tiriti partners, then it cannot always be, as the Hon Kelvin Davis described at the conference, ‘Māori crossing the bridge to the Pākehā world’. It must be matched by ‘Pākehā crossing the bridge to the Māori world’.

This is what the Tiriti partnership calls for.

It has been fantastic to spend the past few days with the Te Akatea Māori Principals in Auckland.

The NZPF leadership team attended not least to affirm our respect and admiration for the skills and expertise of Māori principals in Aotearoa but also to cross the bridge to Te Ao Māori and be learners within this conference that is by Māori, for Māori.

It was a powerful experience.

As a Pākehā, I was in the minority. It was my cultural sense of self that was challenged. I was the one having to adjust. I was the one feeling the prick of difference when we stood to sing the many waiata without always knowing the words. I experienced the frustration of trying to make sense of the kōrero at the pōwhiri, piecing together the words and phrases I recognised, without a sense of context or meaning of the oratory, of trying to guess the humour when laughter roiled the wharenui.

While never made to feel uncomfortable by others, it was my own sense of inadequacy that was confronting. I was, on some occasions, a fish out of water.

And how healthy is that!

It benefits Pākehā to cross the bridge to Te Ao Māori and to experience the dissonance of being in the minority. If we are to truly grow as a country linked in partnership by Te Tiriti then Pākehā must learn to live in the Māori world.

As part of a dominant colonising culture, the onus is on every pākehā principal to step up to this challenge.

For the sake of the young people in our schools and particularly Māori tamariki in mainstream English medium schooling, it is vital.

If we are to truly turn around the inequities in the system and do our absolute best for Māori youth then we need to ensure that every school is not a reflection of the largely mainstream English medium society we live in but rather a place where Te Ao Māori is experienced in a way that is culturally sustaining and valued.

Dr Papaarangi Reid has set forth a wero.

If you are a Pākehā principal, then I encourage you, as ‘lead learner’ in your community, to respond in a personal way by stepping across into the Māori world. Power up your own capacity to lead the design and delivery of education that responds to Māori learners’ needs, sustains their identity, language and culture and demonstrates the value and relevance of Māori culture to all learners.

Māori have a right to have their highest aspirations met and every principal has a stake in making that happen.

That is true partnership!

Ian Narev - facilitator

Billie-Jean Potaka Ayton - Having a strong vision, values need to reflect hauora. Building resilience means we need to consider and support our whole community! How do we maintain relationships? We need to value them, make eye contact, be interested in them.

Nina Hood - social emotional well being in our ability to learn. If we're not in a state of well being we cant be functioning at our best. Going back to some of the basics - creating a sense of social connection, strong relationships helps that sense of belonging. All of our young people have access to learning - through devices, is just the first step. Provide the resources. We need to develop measures to ensure we are providing good practice, monitor how we're going. Lots of ideas are shared but not the evidence of how well they've worked. Whats the evidence to show it's made a difference.

ASB - Sarah-Jane Whitehead - (previously Air NZ) Hauora & wellbeing is an important part of the culture of an organisation. More likely to form great relationships. The relationships we have with others is important but the relationship we have with ourselves is the most important and what we bring with us to our working environment. Making 'real' connections - how are you? Really?